More than four years have elapsed since I began collaborating with Patrick Bowen on the transcription, annotation, and biographical sketches for Letters to the Sage. But only last week did I finally get to Osceola, Missouri where Thomas Moore Johnson, Sage of the Osage, was born and spent most of his life. This visit followed the biennial convention of the Church of Light in Albuquerque, where a three hour preconference was devoted to Johnson and his correspondents. That presentation will be the source of several future updates to this blog. After the conference and before the visit to Osceola, I was able to meet Patrick Bowen at last after four years of collaboration, while visiting friends in Colorado.

I am very grateful to Mary Ann Johnson Arnett, a great-granddaughter of Thomas Moore Johnson, and her husband Jim Arnett for welcoming me to their Kansas home where they have collected memorabilia of the Johnson family and St. Clair County that whetted my appetite for the next day’s visit to Osceola. Before visiting the Johnson Library and Museum, the Arnetts took me to the St. Clair County Historical Society Museum just off the quaint town square. Welcoming us to the museum was Osceola resident and author Meredith Anderson, who with his wife Linda has written more than a dozen books many of which focus on 19th century Missouri. Downstairs exhibit space is broken up into several rooms, one of which is devoted to the Johnson family of Osceola, which include the wedding dress of Alice Barr Johnson, wife of TMJ, and a top hat that he wore. The upstairs of the former church building contains a large meeting hall, and the picture above shows Jim Arnett in the meeting hall. On the way to the Johnson Library and Museum, we stopped at the cemetery where Thomas and Alice Johnson are buried, next to the gravesite of their son and his wife.

We then proceeded to the Johnson Library and Museum which overlooks the former Osage River which is now a branch of Truman Lake. I have previously posted a YouTube video of Tom Johnson’s tour of the building, but having him lead me through the buildings in person was a great honor and a memory I will keep the rest of my life. At the end of the tour we all had an unexpected surprise from Larry Lewis, whose collateral ancestor Edwin Lewis is mentioned in the Letters as the only Osceola friend of TMJ to follow him into both the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor. Larry is author of a new history of Osceola, and just that morning he had learned by email that his book had been nominated to the State Historical Society of Missouri for best book of the year on Missouri history. I have just gotten back home and not yet begun the book, but Larry pointed out to me on page 90 he mentions Letters to the Sage, names Patrick and me as coeditors, and gives publishing information. This is a big milestone for us, the first new book in which LTS is mentioned. I would have expected it to be in some academic tome but being mentioned in a book about Osceola from someone intimately acquainted with the TM Johnson descendants is ten times more gratifying. Before heading back home I enjoyed lunch with Larry and his wife Ruth and the Arnetts within sight of Osceola’s town square, and learned even more about the town’s history. Here is a review of the new book.

Part 2: after arriving back in Virginia I read Larry Lewis’s book and added the following remarks:

Any small county seat would be fortunate to have its stories told by a native with Mr. Lewis’s qualifications. A descendant of the earliest settlers of St. Clair County, he spent ten years of childhood there before being relocated by his father’s wartime employment in Connecticut, and then spent most of his adult life elsewhere. Returning for good after retirement from the Episcopal ministry in 1997, he has been involved in many aspects of town life, including becoming a founding board member of the Johnson Library and Museum established in 1999. His accounts combine the nostalgic glow of family memories and objective description of disasters and decline following the 1861 burning of the town by Kansas Jayhawks and the creation of Truman Lake in the 1970s which ruined what had once been a lively waterfront district on the Osage River.

Chapter 6, “Emily’s Cat,” opens with a description of his first cousin Emily Johnson’s pet Iamblichius, a name with which Lewis was unfamiliar until decades later when he developed an interest in her grandfather Thomas Moore Johnson. Although TMJ was long gone by the time Larry arrived on the scene, “Miz Moore Johnson,” his widow Alice, survived until 1948 and is fondly remembered to this day. The chapter focuses largely on the life and work of TMJ, and includes a description of the varied scholars and writers who have taken an interest in him in recent years. These passages are excerpted from pages 89 and 90:

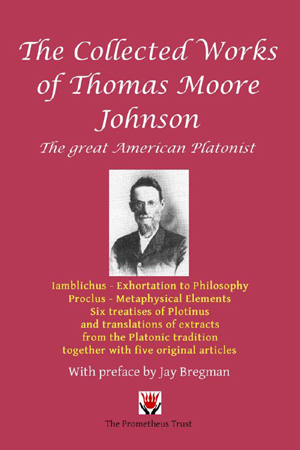

Word about Thomas Moore Johnson is getting around. Scholars on the east and west coasts and parts between are seeking information with a view to writing about the mystical phase of Johnson’s thinking. The scholar K. Paul Johnson in Virginia has documented Moore Johnson’s 1880s relation to the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor [in this blog-KPJ]…Far to the west, in southern California, poet and musician Ronnie Pontiac published a novella-length study of Thomas M. Johnson in the March 19, 2013 issue of Newtopia Magazine…Johnson is cast as a hero in an article by Patrick D. Bowen published the following year…for the journal Theosophical History…Here’s the opening sentence of Bowen’s conclusion: “This article has, hopefully, demonstrated that a number of key developments in American esotericism can be traced to Missouri in the 1880s and that Thomas M. Johnson was a key player in all of these.” Classicist Jay Bregman at the University of Maine, a specialist in the influence of Neoplatonism on the thought of New England Transcendentalism and its offshoots, in his article “Thomas M. Johnson the Platonist” explains the attraction of devotees of the esoteric for Johnson and his Neoplatonist friends…across the Atlantic in Great Britain..the Prometheus Trust published in 2015 the Collected Works of Thomas M. Johnson, the Great American Platonist…Near the beginning of 2016, Patrick Bowen and K. Paul Johnson published Letters to the Sage…

In his book published later in 2016, Mr. Lewis brings the unique perspective of an Osceola resident with family lies to the Johnsons to his own work which combines memoir, Civil War history, ecological commentary, and thoughts about the present and future of his home town. I highly recommend the book to anyone who has taken an interest in Thomas Moore Johnson.