India’s capital provided a unique opportunity to trace the course of 19th century history as a prelude to the freedom movement which led to independence. The first night in Delhi, my friends and I went to the sound and light show at the Red Fort. This magnificent spectacle sweeps through 400 years of history, culminating in national independence in 1947. The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 was particularly emphasized, as the Mogul Emperor of the time lived at the Red Fort. Throughout my stay in Delhi, I was surrounded by symbols of the greatness of the Indian nation. Far more than Bombay, Delhi gives the Western observer a sense of hope for India’s future. It is a clean, hard-working, orderly city in which the beggars and con men of Bombay seem a million miles away. In Bombay, I was surrounded by reminders of the colonial past. Since my goal was to retrace the steps of the T.S. Founders, this was an appropriate starting point. But in Delhi I was confronted continually by symbols of India’s pre-colonial past and its future as a great independent nation. Faith in India’s future was the motivating factor for the Mahatmas’ sponsorship of the Theosophical Society. In Delhi I began to see their lives in context of inevitable progression toward the national destiny.

Although my hypotheses have been rejected by one Theosophical publisher as providing an “all-physical” solution to the mystery of the Masters, the evolution of a nation is ultimately a spiritual process. The exhibitions in the Nehru Museum lead one through this process as it is seen in the life of one man. ,Jawaharlal Nehru, who met Annie Besant when he was 13 and joined the T.S. immediately, was the first leader of free India. His descendants have governed the nation for almost all the years since his death, but shortly before my arrival Rajiv Gandhi lost his bid for reelection. Nehru’s father, Motilal, was also a Theosophist, and Mohandas Gandhi’s link with the T.S. was a crucial element in his awakening as a leader. In his student years he visited the T.S. in London, met HPB, and first read the Bhagavad Gita there in a Theosophical translation into English. The roles of Annie Besant and Mahatma Gandhi in the Indian freedom movement are well documented in the Nehru Museum. Thus my researches in the adjacent Nehru Library were carried out amid many reminders of the Theosophical contribution to India’s destiny.

The Kashmir State: A Biography of MaharaJa Gulab Singh 1792–1858, by K.K. Panikkar, I learned that Ranbir’s mother was a Rukwal Rajput married in 1809.(19) Unfortunately, the origin of the Rukwal tribe was nowhere to be found. ‘

Arva Samaj in the Freedom Movement: 1875–1918 by K.C. Yadav and K.S. Arya reveals the deep involvement of Swami Dayanand’s followers in nationalistic agitation. Part 2, “Eminent Arya Freedom Fighters,” .includes a portrait of Shyamji Krishnavarma, the brilliant scholar and leader of the Bombay Samaj who remained loyal to the T.S. Born in 1857 to a Brahmin family in Kutch, he was educated in his home town of Mandavi before completing high school in Bombay. There he took a prize in Sanskrit, which was an omen of his future career. In 1875 he married a rich merchant’s daughter, and shortly thereafter was involved in the founding of the Arya Samaj in Bombay. In 1877-78 he did a propaganda tour through Western India for Swami Dayanand. After being introduced to the English Sanskritist Professor Monier Williams, he went to England in April 1879 at his invitation. He completed a B.A. in 1883, returned home to India and was Diwan at Ratalam for several years. In 1888 he became a lawyer at Ajmer, and later pursued this career at Udaipur. In 1895 he was dismissed from the position of Diwan in Junagarh, for reasons involving a conspiracy of British local officials. Krishnavarma returned to London in 1897, and two years later he became politically active on behalf of the Boers. In January 1905 he founded The Indian Sociologist, an “organ of freedom and of political and social reforms.” Later in the same year he started the Indian Home Rule Society. In 1906 he opened India House in London, but left :for Paris in 1907 due to fear of the “police noose very close on him.” In 1914 he went to Geneva where he continued the struggle for Indian freedom until his death March 31, 1930. Thus the young man who was a devoted disciple of the Theosophical Masters became in maturity yet another freedom fighter who had to flee British wrath and find French protection. The details of his connection to the Mahatma figures proposed in this book remain hidden; however the facts as stated above qualify him as one of the adepts in the broad definition which has emerged in the course of investigation.

A biography of another member of the Masters’ secret world is found in Advanced Historv of the Panjab, Vol. ll, by G.S. Chambara. It provides the hitherto unknown information that Professor Bhai Gurmukh Singh revived the Singh Sabha movement in 1876, three years after it was founded by Thakar Singh Sandhanwalia. Apparently the group had become virtually defunct until Bhai Gurmukh Singh took an interest in it. Born in 1849 th son of a poor cook, the young Sikh showed academic promise which was recognized by Prince Bikram Singh of Kapurthala, his home city. By 1876, when he joined forces with Thakar Singh, he had become a language scholar. Chhambara writes “It was a result of their joint efforts, that the Panjab University Oriental College, which had been opened in 1876, introduced also teaching of the Panjabi language in 1877; Professor Singh himself being appointed a lecturer for the subject.” Bhai Gurmukh Singh founded the Lahore Singh Sabha in 1879 while Thakar Singh remained in Amritsar. Both were leaders of the progressive faction of the group, opposed by the conservatives led by Khem Singh Bedi.

The Punjab University may well have been the first project in which Thakar Singh and his disciple Bhai Gurmukh Singh were associated with the Maharaja of Kashmir. Ranbir Singh’s patronage of the university is mentioned in the first chapter of Book III, where it is recorded that we was honored as its First Fellow for his patronage of language studies and translations. Bhai Gurmukh Singh, it should be recalled, was on terms of intimate friendship with Olcott as late as 1896. It was not until I reached Adyar that I found evidence of how early and how important were his links with the T.S. But in coming to recognize the close bond between the founders of the Amritsar and Lahore Singh Sabhas, I also was obliged to reevaluate the character of Baba Khem Singh Bedi.

Gopal Singh’s History of the Sikh People 1469-1988 gives a much more detailed portrait of Khem Singh than was available in sources previously consulted. The author writes:

Born in 1832, in the house of S. Attar Singh Bedi, at Una, (in the district of Hoshiarpur) and a great grandson of Baba Sahib Singh Bedi, he was a great friend of the British Government. is jiagir was, therefore, continued after the annexation of the Panjab. In 1857 too, he was of much use to the Government and was later awarded large tracts in the district of Montgomery…He opened many women’s educational institution’s, though female education was not much encouraged in those days. He helped develop the newly-formed district of Montgomery. Due to his vast influence, he was knighted and was nominated member of the Council of States…He died in 1904, leaving four sons.

Relations between Khem Singh, Thakar Singh and Bhai Gurmukh Singh were apparently strained for some time before the latter two took up the cause of Dalip Singh. The identity of Khem Singh as the Chohan seems less certain in light of facts uncovered in the Nehru Library. For example, the Amritsar Akal Takht, under Khem Singh’s influence, excommunicated Bhai Gurmukh Singh on March 18, 1887, just as Dalip Singh went to Russia. Most Singh Sabhas sided with the Lahore progressives led by Bhai Gurmukh Singh; most orthodox Sikhs did not. Although Khem Singh Bedi seems to have thoroughly opposed Thakar Singh and his followers once the Dalip Singh plot was initiated, after Thakar’s death he changed his position as described in chapter 2.

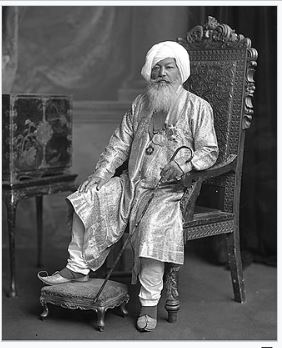

My search in the library uncovered six sources which were particularly enlightening on the subject of the Masters of the T.S. The Gulabn_gma _2f_Diwal_KirEal Ram, a biography of Gulab Singh written during the reign of Ranbir, was translated from Persian in 1977. Sukhdev Singh Charak, biographer of Ranbir Singh, translated and annotated the text. Its title page calls Ranbir “the benevolent and exalted, the diamond of the diadem of Government, the lustre of the sword of kingship, the decorator of the crown and throne, the ferocious lion of battle and war…”(17) This source identifies five wives of Gulab Singh, but not which one was mother of Ranbir. This was of interest due to a note in Olcott’s diary written when passing through Jaipur on the train. As he passed a castle, he commented that this was where “my Father ‘s mother was born long ago.” In Founding of The City of Amritsar: A Study of Historical. Cultural, Social and Economic Aspects. edited by Dr. Fauja Singh, includes a chapter entitled “Amritsar and the Singh Sabha Movement” by Gurdarshan Singh. He writes:

“The leaders of the Amritsar Singh Sabha, being drawn almost exclusively from the rich and aristocratic classes of the Sikhs, were not ready to shed off their old prejudices against the low caste Sikhs…who were allowed to visit the gurdwaras only at specified hours… Baba Khem Singh Bedi tried to wield absolute control over the activities…he aspired for reverence due a guru…The radical among the Sikhs dissociated themselves…The gulf between the two parties ultimat ly resulted in the formation of an independent Khalsa Diwan at Lahore in 1886.”

Thakar Singh, it may be supposed, was well respected by the radicals of Lahore by this point due to his intrigues with Dalip. Despite his status as founder of the Singh Sabha, his anti-British activities had alienated him from his former Amritsar colleagues. Later in Adyar I unearthed evidence which made it perfectly clear that Blavatsky and Olcott were allied with Bhai Gurmukh Singh and against Baba Khem Singh Bedi from the beginning of the Theosophical work among the Sikhs. But while my research on the Singh Sabha at the Nehru Library provided the groundwork for later explorations in Adyar, in March 1990 the Punjab was off limits to foreign travelers. Crossing the Pakistani border to Lahore was even less feasible. So after five days in Delhi, I proceeded directly to Jammu, keenly regretting that Amritsar and Lahore could not be included in my investigations.